Weekend To-Do List

6/9-6/11

1. CREDO Mania

READ/LISTEN: Stanford’s Center for Research on Educational Outcomes (CREDO) found that public charter schools produce stronger gains than traditional public schools. These gains were true of most vulnerable subgroubs, including Black students, lower income students, Hispanic students, and ESL students. The exception was special education students, who performed worse in charters. The regional differences were also notable. States with strong and healthy authorizing environments (New York, Tennessee, Rhode Island) killed it, while some of the more loose authorizing states performed worse.

Haters for years would cite earlier versions of this study (when they had less flattering things to say about the schools) to discredit charter schools. Of course, charter critics have now turned on CREDO. Jonathan Chait in New York Magazine has a great write up of that dynamic, with a rousing rebuke of a standard liberal critique of charters:

Even those liberals who implicitly grant that charter schools can make a positive difference for minority students tend to linger on the limits of what a better education system can accomplish. There is almost a mania for refuting the proposition that education reform will eradicate poverty and inequality. Here are just a few headlines turned up by a simple Google search: “Education Alone Won’t Solve Poverty, Social Isolation, and Resentment”; “Education Alone Won’t End Income Inequality”; “Why Education Won’t Solve America’s Inequality Crisis”; “Education Can’t Solve Poverty — So Why Do We Keep Insisting That It Can”; “No, Education Still Won’t Solve Poverty”; “Better Schools Won’t Fix America.”

I can’t think of any social intervention that is so frequently measured against the baseline, “Does this single-handedly eliminate poverty/inequality?”

So, fine, I agree. Education alone won’t end inequality or poverty or save America. Neither, for that matter, will universal health care or full unemployment or ending racism. So what?

Rikki and I discussed the findings on this week’s episode of Lost Debate here. Read the full report here, an overview of the findings from Kevin Mahnken at The 74 here, and Chait’s analysis here.

2. Student-on-Teacher Violence Surges in Nevada

READ: Scott Calvert documented the alarming rise of student violence against teachers in Nevada for the Wall Street Journal. Northern Nevada’s Washoe Country recorded 7,418 violent events in the first 110 days of the school year, the highest amount in five years. The situation has reignited the debate over restorative practices, and last week Gov. Joe Lombardo rolled back a 2019-era law that required a restorative justice plan before removing a student from a classroom or school.

Jamie Lindsey, 28, spent her birthday in 2021 at the hospital after a girl who was fighting jerked her head back, striking Lindsey’s face hard enough to bloody her nose. Since then, Lindsey has mostly let co-workers like Malaterre lead the response to altercations. She has worked with a counselor to process the anxiety she feels whenever she hears a hallway ruckus.

“I’m freaking out on the inside, but on the outside I can’t show that to the students. I can’t. I have to come back in and do my job,” she said on a spring morning as students filed into the brightly painted classroom she and Malaterre share. “I signed up as a teacher, not as a police officer.”

Read more here.

3. No Fun in the Sun: Summer Camp as Child Care Leaves Parents Struggling

READ: School’s out for summer, and the parents are not okay. Lydia Keisling wrote for Bloomberg about the current state of summer camps, the challenge of finding (and staffing) sufficient child care for July and August, and how the season has become the latest face of America’s ever-growing class divide.

This is summer camp in 2023, though the term “summer camp” itself is maddeningly unspecific, describing a host of programs that include sleepaway camps and day programs such as those offered by recreation and parks departments or the YMCA. The options have become increasingly baroque and specialized over the years (think space camp, orchestra camp, fine arts camp, coding camp, social media camp). It’s all, frankly, a mess: There are no set prices, no consistent dates, no agreed-upon time to register. Cheaper camps might have later registration dates, but they also have more competition for spots. Many camps don’t cover the typical workday (9 a.m. to 3 p.m., or even 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., is pretty standard). You can pay more for aftercare in some cases but not others. Specialty camps sound great but often offer only one- or two-week sessions.

Read more here.

4. Broken Discourse Around the SHSAT

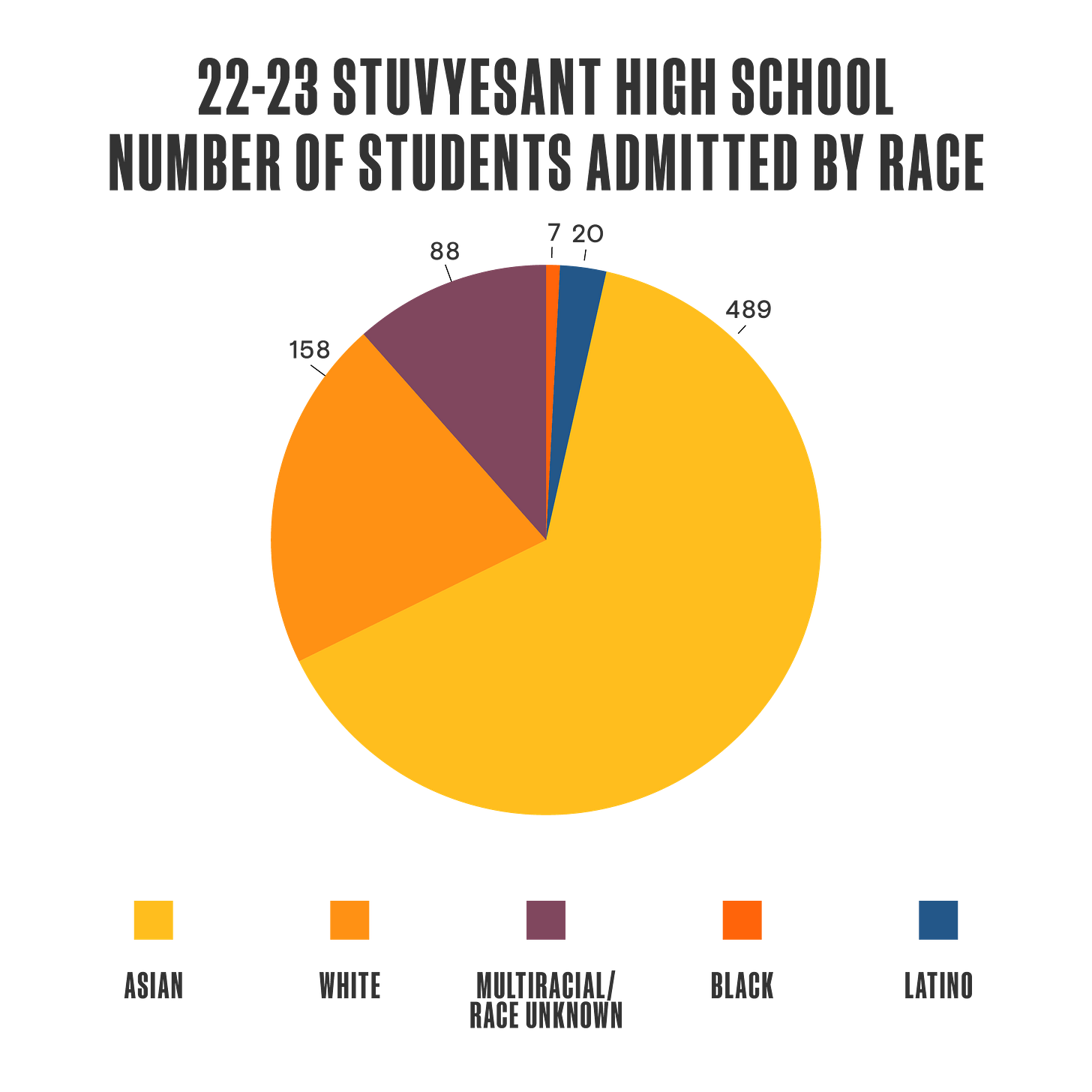

READ: Seven Black students received an offer to attend Stuyvesant High School in New York City this year, reigniting the annual debate over the admissions processes for the City’s eight specialized high schools. Troy Closson broke down the demographic data for the New York Times.

Critics of the current admissions process have called for the elimination of the schools’ entrance exam, the SHSAT, a position championed by former Mayor Bill de Blasio. Stuyvesant alum Sheluyang Peng took to the pages of Tablet in response, urging New Yorkers to remain the last holdout in the war against American meritocracy:

An array of acronyms fill the front windows of each tutoring center: SHSAT, PSAT, SAT, ACT, AP. While some immigrants may not have a full grasp of the English language, they can still understand that these acronyms serve as symbols of upward mobility—and of a meritocracy where access to elite spaces is not about knowing the right people and signaling the right cultural cues, but about competency on an exam that anyone can pass with enough studying. That’s what drew Jewish immigrants in droves to specialized high schools decades ago. And in an era where elite colleges consistently rank Asian applicants lower in “personality” metrics—a loophole that allows them to impose quotas and cap the number of incoming Asian students in the name of increasing “diversity”—it’s no wonder why many Asian immigrants are working to preserve standardized testing.

Read more from Peng here.

5. Inequity in Special Ed

READ/LISTEN: The spotlight was on New York City’s Department of Education this week. Beth Hawkins at The 74 highlighted the DOE’s ongoing inability to meet the needs of the City’s nearly 250,000 students with disabilities. In the past two months alone, investigations revealed that 37% of NYC preschoolers with disabilities and 64% of bilingual special education students have not received their required services. Thousands of families are waiting for reimbursements for private school tuition and as of November 2021, 16,000 children are stuck in a bottleneck of impartial hearing cases.

The system was already at a standstill, say critics. But now, a reservoir of children whose confirmed or suspected disabilities went unevaluated and unserved during the pandemic threatens to overwhelm it completely. The department struggles to find, heat and cool, and staff enough rooms to hear waiting families’ cases, much less process their reimbursements.

Is there any hope for reform? A special master issued a 127-page report this March with 75 recommended next steps – beginning with two pages of acronyms used by the DOE – but warned the changes will take years to implement.

Rikki and I discussed this crisis on a November episode of Lost Debate. Listen here, and read more from Hawkins here.

6. Will a Religious Charter School Alter Education as We Know It?

READ: The nation’s first religious charter school was approved in Oklahoma on Monday. In a 3-2 vote, the Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board approved St. Isidore of Seville Catholic's re-application for their online public charter school. This comes after the Board denied the original application in a 5-0 vote in April, amid concerns that the state statutes and Oklahoma Constitution prohibit the use of public money for religious purposes. Matt Barnum over at Chalkbeat analyzed the decision’s potential ramifications:

If religious charter schools become a reality, they could rejuvenate religious education, particularly Catholic schools, which have been losing students for many decades. Such schools could continue the successful conservative campaign to allow more public funding to go to religious education. They could lead to fewer students, and thus less funding, for public schools. Charters of all types could be deemed private schools for legal purposes, reducing anti-discrimination protections for students and teachers.

This is a startling possibility. Charter schools have long enjoyed bipartisan support because they were seen as a compromise to private school vouchers. Advocates promoted charters as innovative options within the public sector. Leading national charter organizations maintain this view and oppose religious charter schools. But it’s not clear they will be able to keep a hold on their own movement.

The decision is almost certain to go through the courts and could take years to play out. Read more here. We also discussed this case on a December episode of Lost Debate. Listen here.

7. On Teaching in a Red State

READ: The backlash against the backlash has gained steam beyond Florida. High school English teacher Anne Beatty shared her experience as an educator and parent speaking at a school board meeting in her hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina:

I begin, “I come to you tonight with this message: Our students are stronger and more resilient than we might think. We must teach our children the whole truth about our country’s history of racial injustice. They are strong enough to handle this truth. In fact, they’re hungry for it. And when students realize they have not learned the full truth, they feel betrayed.”

I explain my own sense of betrayal when I learned about historical events only as an adult, and I ask the school board members to trust teachers to facilitate these conversations, to teach students how to think, not what to think.

Read Beatty’s Longreads piece here.

8. The End of College Rankings, Continued

READ/LISTEN: Nick Anderson and Susan Svrluga of The Washington Post reported on Columbia University’s decision to pull out of the U.S. News and World Report Rankings. Columbia is the latest in a string of elite institutions denouncing the publication:

University Provost Mary C. Boyce and three senior academic deans lamented in a statement the “outsized influence” that rankings may have with prospective students and “how they distill a university’s profile into a composite of data categories. Much is lost in this approach.”

We discussed this trend on a March episode of Lost Debate, and I took to the pages of this very publication to argue that the U.S. News rankings are better than no rating system at all.

9. Meet Denver’s Mayor-Elect

READ: Former school principal Mike Johnston will be Denver’s next mayor after winning 55% of the votes in the city’s runoff election earlier this week. How will the former educator support Denver’s kids and families? Erica Meltzer at Chalkbeat shared excerpts from a May mayoral forum on the topic:

Q: As indicated by the most recent state testing data, Denver Public Schools is not adequately supporting academic achievement among students of color or those who are low-income. What role can the mayor play in addressing the equity gap among students?

A: It starts with the belief that Denver students are all of our responsibility. One of the most important ways that we can do that is looking at all of the learning time right now that happens outside of the school building. All the things that happen outside of 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., where we know young people’s access to after-school programming to summer school programming to tutoring and arts and athletics and science camps … drive a big part of the passion that makes you who you are as a young person.I want to expand programming to make sure young people, particularly those on free and reduced [price] lunch, have access to those opportunities to help them find their passion.

Read more here.